Chasing Cyber - #21 - Lattices

Research, Timing Attacks, and QKD

Welcome to the 21st edition! This week we look at lattice research, timing attacks, and claims of QKD dominance.

Lattices, Lattices, and More Lattices

Last year, it seemed like every third cryptography paper was focused on lattices. So I crunched the numbers to find out.

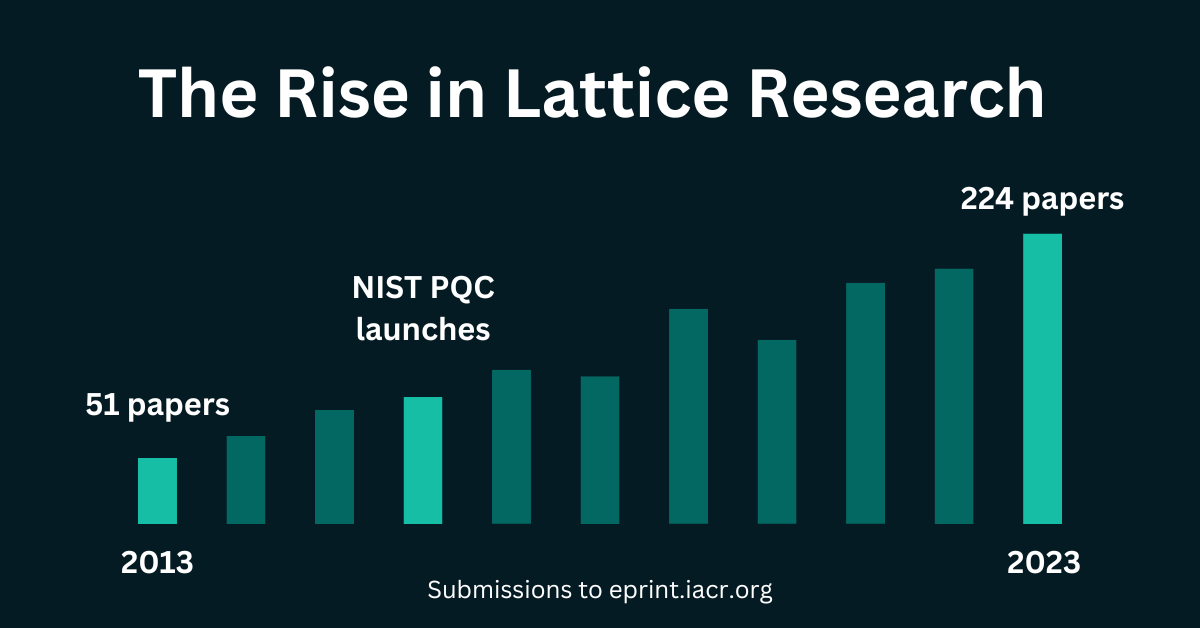

I wasn’t imagining things. We’ve seen a huge increase over the last 10 years, no doubt helped by the NIST post-quantum competition.

By counting the papers submitted to the IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, we can see a rise from 51 papers in 2013 to a staggering 224 papers last year.

This should be exciting news to cryptography fans. Lattices will play a critical role in cryptography going forward. The more we know about them, the better.

The Boy Who Cried Kyber

Did you notice the scary post-quantum headlines last week?

“KyberSlash attacks put quantum encryption projects at risk”

“Vulnerabilities reported in post-quantum encryption algorithm”

Yikes! It sounds like a NIST PQC algorithm winner is broken, right?

Fortunately, Kyber isn’t fundamentally broken. But unfortunately, we’re going to see a lot of these headlines over the next year.

Last week’s news was about the KyberSlash attack. (Don’t you miss the old days when attacks didn’t get their own websites and brand names?). KyberSlash is a timing attack affecting some implementations of Kyber.

Timing attacks occur when the runtime of a program is dependent on a secret value, such as a private key or a password. Attackers carefully measure the response time of a program and use this to learn about the secret value.

Consider a simple password-checking algorithm. A naive implementation would compare each character of the entered password against the real password and fail when they don’t match. However, this means the program will take slightly longer to respond when you guess the first letter correctly. An attacker can use this to guess the entire password.

KyberSlash is a timing attack based on division operations (hence the suffix “Slash”). In several public implementations of Kyber, a division operation was performed using a secret input. In some computing platforms, this will leak timing information.

It’s great that this has been spotted, and duly fixed. But it’s not something to panic over, because it doesn’t represent a fundamental weakness in the Kyber algorithm.

It’s All Quantum on the Eastern Front

China and Russia claim to have demonstrated quantum key distribution (QKD) over 3,800km.

The QKD exchange used the “Mozi” satellite, which China launched in 2016. To my knowledge, this remains the only QKD satellite currently in orbit, although several others are being developed around the world.

In the alleged demonstration, key material was exchanged with a ground station near Moscow and another station in Urumqi, a city in northwest China. Once the keys were established using QKD, communication was established between the ground stations using terrestrial non-quantum cryptography.

Naturally, we should take news emerging from these countries with a pinch of salt. However, it seems plausible this experiment occurred, and it should serve as motivation for continued efforts to launch western QKD satellites in the years ahead.